Down the hill from Hampstead village is Belsize Park still regarded as part of Hampstead, it has the same post code of NW3, and was in the Metropolitan Borough of Hampstead before both became amalgamated in 1965 to become the Borough of Camden. The area began to attract artists when nine studios were built by Thomas Buttesby in Steele’s Road, Belsize Park, between 1871 and 1879 and close by, The Mall Studios, behind Park Road, now Parkhill Road, were built about the same time. Early occupants of these and other dwellings in the neighbourhood included the WWI artist and landscape painter George Lausen (1852 – 1944), the illustrator Arthur Rackham (1867 – 1939), and also Walter Sickert before he moved down the hill to Camden. However Belsize Park’s heyday as an artistic centre was in the 1930s. The sculptor Barbara Hepworth and her husband John Skeaping moved there in 1927; Hepworth was to become one of the most renowned and innovative sculptors of the 20th century. Like the earlier artists with Hampstead connections, she became interested in the modern art movements which had begun on the continent, and was one of the first British sculptors to produce abstract works, hollowing out shapes and attaching great significance to the negative spaces thus created.

Barbara Hepworth was born in 1903 in Wakefield, Yorkshire. In 1920 she won a scholarship to Leeds School of Art where a fellow student was Henry Moore. She continued her studies at the Royal College of Art from 1921 to 1924 and after leaving she travelled on a one-year scholarship in Italy with Skeaping who had been a fellow student and was also a sculptor. They married in Florence in May 1925 and returned to London in November 1926. In 1928 they moved into No 2 The Mall Studios and the following year their son, Paul, was born.

By 1931 Hepworth and Skeaping had drifted apart, and her meeting with Ben Nicholson that year sounded the death knell of their marriage. In 1933 she divorced Skeaping and in 1934 gave birth to triplets, two daughters and a son, with Nicholson. The mind boggles at the thought of the pair along with their triplets and her son Paul all living in a small studio – their precarious financial position inhibiting a move to somewhere larger. Hepworth and Nicholson were married in 1938 after his divorce from the painter Winifred Nicholson. In 1939 when WWII was imminent they decided to move to St Ives, Cornwell. First they lived in a house belonging to the art critic Adrian Stokes, then in 1942 they moved into a larger house with a sheltered garden which enabled Hepworth to begin working outdoors for the first time. In 1949 they bought Trewyn Studio where Hepworth lived till her death. ‘it will be a joy to carve in such a perfect place …….. the garden sheltered by tall trees and roof tops so that I can work outdoors most of the year’, she declared on finding the studio. In 1950 her work was shown in the Venice Biennale after which she began to be recognised internationally.

In 1951 Nicholson and Hepworth were divorced and in 1953 her son Paul, who had been a professional pilot, was killed in an air crash. In order to come to terms with this crisis in her life Hepworth journeyed to Greece and wrote while there ‘ Sculpture to me is primitive, religious, passionate and magical -always magical – always affirmative’. The following year a major retrospective of her work was held at the Whitechapel Gallery. Monolith, a large limestone sculpture dating from this time stands in the grounds of Kenwood House, Hampstead Heath.

In 1964 Hepworth was diagnosed with cancer of the tongue for which she was successfully treated but from then on she was beset by ill health exacerbated by breaking her femur in the Scilly Isles in 1967, but despite poor mobility from then onwards she doggedly continued working. In 1968 the Tate held a major retrospective of her work. Unfortunately the tongue cancer she had suffered due to heavy smoking had not deterred her habit and in 1975 she was smoking in bed when it caught fire and she was burned to death. A year later Trewyn Studio opened as the Barbara Hepworth Museum.

Barbara Hepworth may have been the most famous of the artists in Belsize Park in its heyday, but there were many others. The art critic Herbert Read who himself lived at the Mall Studios from 1934-5 described the neighbourhood as ‘a nest of gentle artists’.

The expressionist painter, Oscar Kokoschka, had been outspoken in his opposition to the Nazi regime and many of his paintings had been destroyed by them, so in 1938 he fled to London from his home in Austria-Hungary and moved into a studio at No 45 King Henry’s Road, NW3, near the Steele’s Road studios. Kokoschka had an intense dislike of London so throughout the war although he and his wife kept a base in London, during the summer months they lived in Ullapool, in Wester Ross, Scotland , which must have been the perfect antidote. In 1946 they moved to 120 Eyre Court, Finchley Road, where a blue plaque commemorates him. In 1953 they left London and settled in Montreux, Switzerland where Kokoschka lived until his death in 1980 at the age of 93.

The WWI artist Richard Nevinson (1889 – 1946) who had been a contemporary of Mark Gertler, Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer and Carrington at the Slade School took one of the Mall Studios in 1939. The Dutch painter Piet Mondrian lived in Paris from 1919 until 1939 but when war seemed imminant he left for London and moved into a room at No 60 Parkhill Road – a blue plaque on the house commemorates him. By all accounts this was a pokey little room which Mondrian disliked intensely and the view of the garden from the window, which would have been to most people its only redeeming feature, particularly erked him, hating the colour green he had banned it from his palette and used only black and white and the primary colours – he complained of the view that it had ‘too many trees’. The final straw came in 1940 when a bomb dropped nearby and he fled to New York where he lived till his death in 1944. Two days after this bomb another was dropped in the same area which happened to trap Henry Moore in Belsize Park tube station. What is one persons nightmare is another’s inspiration Unlike Mondrian, rather than being traumatized by this event Moore was inspired and the next day he began his shelter drawings which became as well known as his sculptures. Moore and his wife Irina lived at 11a Parkhill Road from 1929 to 1940 where a blue plaque commemorates him. In 1941 they moved around the corner to the Isokon block of flats in Lawn Road. This iconic block, built in 1933, was designed by the architect Wells Coates as an experiment in communal living for young professionals of modest means who wanted to dispense with ‘tiresome domestic troubles’. Its services included cleaning, laundry, cooked meals and even shoe shining! If only ……….. ! It still stands and is a grade I listed building. Occupants of the Isokon included writers, architects and artists, the latter included the Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and the designer and Bauhaus member Marcel Breuer, Naum Gabo, Cecil Stephenson and Alexander Calder (1898-1976) who was most famous for his mobiles.

This is the final part of my posts on artists of Hampstead. NW3 is no longer an artists quarter. That ended in the 1950s long before I arrived, accidently, but I think fortuiosly, because I love the area for many things including the tree-lined streets, Hampstead Heath, and not least the plethora of coffee shops – I’m doing this post in one. It is now difficult to keep up with London’s Artists Quarters and sadly artists who are not famous are gradually being priced out of the city altogether. One area where this has happened recently is Shoreditch. Some artists have moved further east to Mile End, while others have gone south of the river to Bermondsey from where they are gradually edging south to Peckham. Oh, and I must not forget Willesden. I may live in leafy, long gentrified NW3 but my studio, along with many others, is on an industrial site at Willesden Junction. Who knows where the next Artists Quarter will be, Perhaps it will be Penge, the butt of many jokes, or the much maligned Croydon.

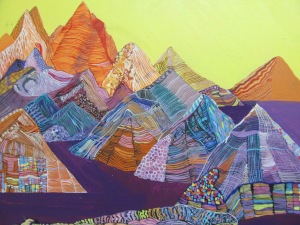

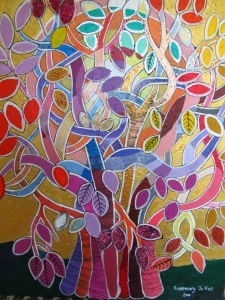

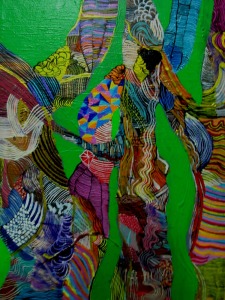

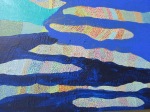

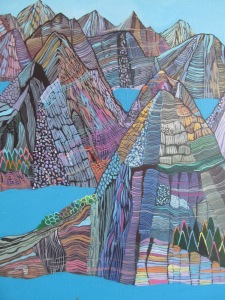

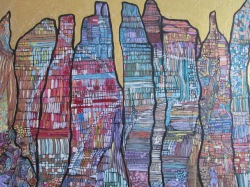

Here are four paintings of mine. As is often the case in my blog they have nothing to do with this post. Also I assure you they are mine, they were just done a long time ago, about twenty years before most of my paintings on this blog. I’m not sure whether I’ve progressed or regressed in my art work, all I am sure of is that it has changed.

1 ANGELS IN THE MOUNTAINS Gouache on paper

2 COY CARP Gouache on paper

3 WATCH OUT! Gouache on paper

4 FROGS IN LONG GRASS Gouache on paper